What Happened to Dropout Rates after COVID-19 School Closures in Ghana?

This blog is the first in a series from PREPARE: a consortium of research organisations from Ghana (IEPA), Kenya (APHRC), Malawi (CERT), Senegal (CRDES), and Pakistan (tbd), all focused on the educational challenges posed by COVID-19.

Like most countries across the world, Ghana closed schools for long stretches of 2020. In this blog, we present findings from a nationally representative household survey carried out in March 2021 on the effects of the pandemic on education in the country. Despite many concerns at the start of the pandemic, we found that (so far) dropout rates are relatively low in Ghana, at just 2 percent of previously enrolled children, which matches pre-pandemic dropout rates. There are important equity concerns, however. Poorer children are at a higher risk of dropping out compared to their richer counterparts, and boys are more likely to drop out compared to girls. We also found that while dropout rates hadn’t risen from their pre-pandemic baseline, many more students were repeating grades.

Ghana has had two waves of COVID, first peaking in July 2020 and the second in February 2021. Cases and deaths have remained relatively low, with an overall official death toll of less than 1,000. Schools closed in March 2020 and gradually reopened at different levels throughout the year until a full re-opening in January 2021 for all levels of education. We carried out the first planned wave of our survey from 8th to 22nd March 2021 across the country.

Following global school closures, experts have raised concerns about learning loss and dropouts. But so far actual data from low and middle-income countries has been scarce. Thankfully, children have been largely spared the direct health effects of the disease, but the pandemic has severely disrupted education. And parents and carers have borne the broader economic impact, which has increased the risks that they will be unable to afford to keep their children in school.

Dropout stayed the same as previous years, but grade repetition increased

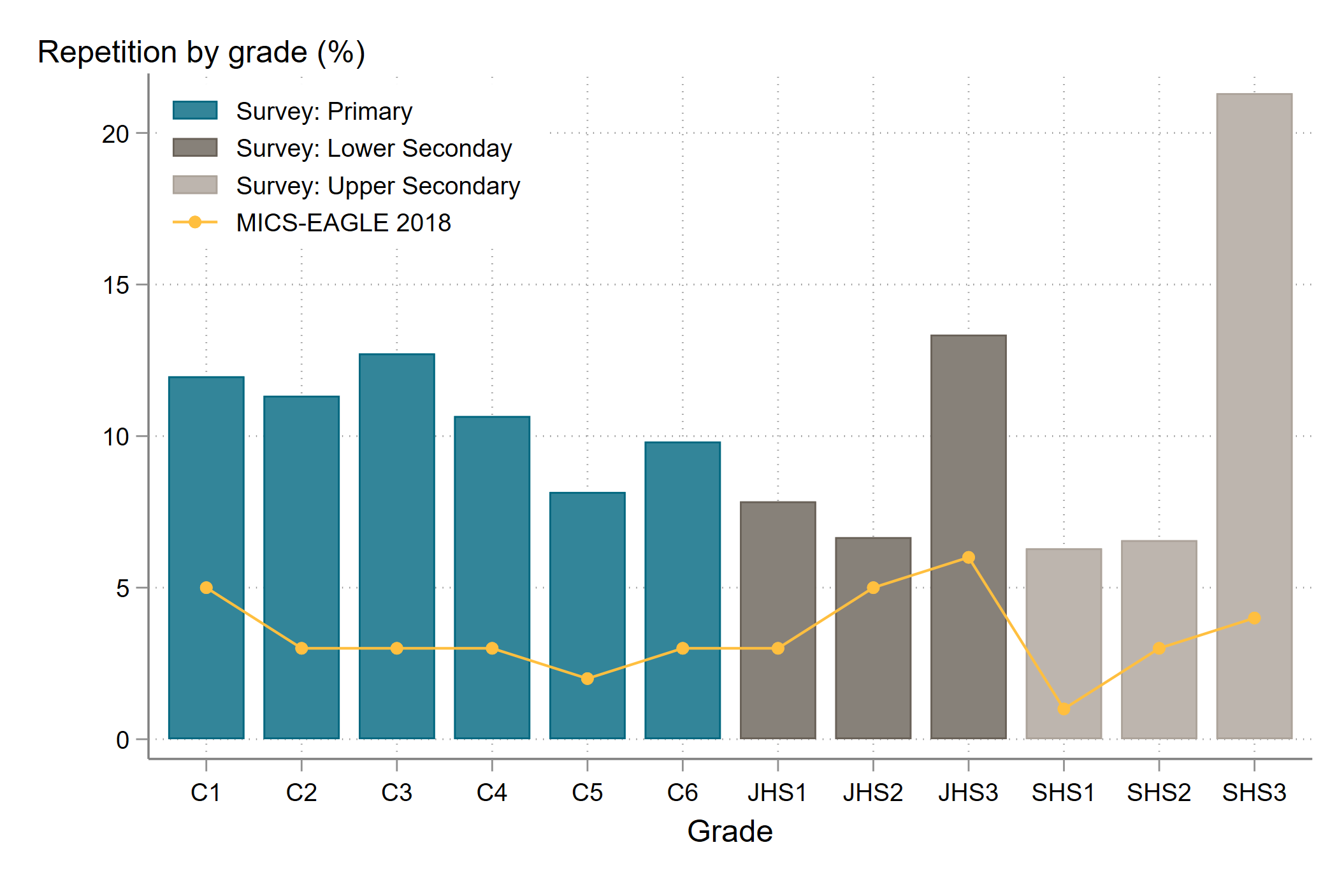

We find that 2 percent of children that were enrolled in the year before the pandemic are not going back to school this year. The highest dropout rates are in key transition grades at the end of primary (C6) and junior high school (JHS3). Compared to survey data from 2018, dropout has stayed almost exactly the same (in comparable grades), falling from 2.1 percent to 2.0 percent. However, we see a much bigger increase in repetition rates, rising across all grades from an average of 3.5 percent in 2018 to 10.5 percent (Figure 3). This is despite the government policy of encouraging grade promotion with any necessary remediation taking place in new classes.

Figure 2. Dropout rates by previously enrolled grade

Note: We define dropout as the proportion of children enrolled in a grade in 2020 who are not enrolled in school for the year of 2021 and have declared they are not going back when school reopens. Children who repeated the year are still considered to be in school. MICS-2018 calculates transition rates rather than dropout rates for class 6 and JHS3, therefore are omitted in the graph on the left. Non-transition rate is the share of children who completed the last grade of the lower school level in the previous year but are not enrolled in first grade of the following school level, divided by the number of children in the last grade of the lower school level in the previous year who are not repeating the last grade of the lower school level in the current year.

Figure 3. Repetition rates by grade (%)

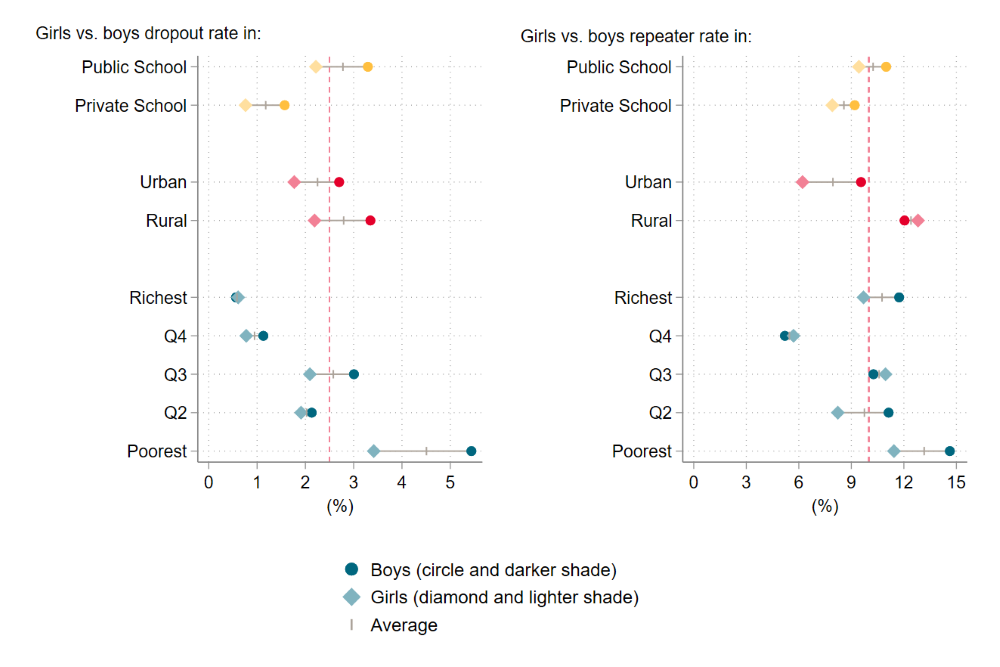

Poorer children were more likely to drop out than richer children and boys were slightly more likely to drop out than girls

Given the role of poverty, location, and gender among other factors affecting decisions to participate in schooling, we further analysed the data to understand the characteristics of those children not returning to school.

Children in the poorest wealth quintile are much more likely to drop out (4.5 percent) than those in the richest quintile (0.5 percent). Boys (3 percent) are slightly more likely than girls (2 percent) to drop out. Children in private schools are less likely to drop out or repeat, and those in rural areas are more likely to (Figure 4).

It’s encouraging that the rate of children leaving school early hasn’t risen overall, but given that dropouts vary across gender, the rural-urban divide, household wealth, and school types—often falling on the more marginalized—it’s important for policymakers to take the differential impact of COVID into account as they chart education recovery plans.

Increases in repetition are normally concerning as they imply a major inefficiency, doubling the time and resources needed to get a child through to the next grade. In the context of nearly a full year of missed school however, a more important risk may be the promotion of 90 percent of children to a new grade that they are not prepared for, setting them up for failure.

As the education ministry figures out how to undo the damage of COVID on schooling, it’s worth considering novel solutions. For instance, for many years the picture was that education in Ghana was male-centric and campaigns were needed to counter that. Given the evident success of those campaigns, and the fact that COVID has disproportionately affected boys’ enrollment, it may be time to consider campaigns focused on some of the drivers of boy’s dropout rates, like child labor.

Stay tuned for more findings from Phase I of our study, including on the effects of COVID school closures on learning, as well as more research from other PREPARE partners on how the pandemic is reshaping education.